In Imperial China, the fate of concubines after the emperor’s death was shaped by a complex web of rank, politics, custom, and dynasty-specific norms. While some were elevated to honored positions, others faded into obscurity—or were swept up in the tides of dynastic change. Their futures were far from uniform, but always reflected deeper social, spiritual, and political structures of their time.

1. The Hierarchy of the Imperial Harem

The imperial harem was not a single group but a strict hierarchy. At the top stood the Empress, followed by various ranks of consorts and concubines. A woman’s fate after the emperor’s death often depended on her position in this order. Those who had borne children—especially sons—stood to gain protection, influence, or even elevation, while lower-ranked women without issue often lost favor and security.

2. Common Fates After an Emperor’s Passing

A. Buried with the Emperor

In early dynasties such as the Shang and parts of the Han, human sacrifice was practiced. Some concubines were buried alive to “accompany” the emperor in the afterlife. This practice, known as xunzang (殉葬), gradually diminished due to humanitarian reforms and changing philosophies, and was formally outlawed in later dynasties.

B. Relegated to Widow’s Quarters

More commonly in the Ming and Qing dynasties, widowed concubines were moved to secluded palaces, such as the Palace of Eternal Longevity. Though well provided for, they lived out their days in relative obscurity, often without further contact with court politics.

C. Becoming Buddhist or Taoist Nuns

For many concubines, especially those without children or political influence, becoming a nun was an accepted and even honorable exit. Some entered monasteries, while others lived in temple-affiliated compounds. This religious transition was often encouraged to allow the court to “gracefully retire” women no longer needed in the palace.

D. Returning to Their Natal Families

In certain dynasties, lower-ranked concubines without royal children might be permitted to return to their birth families. This allowed them to live relatively ordinary lives again, although usually under social constraints such as remaining unmarried. While not the norm, this return to civilian life represents one of the more peaceful outcomes.

E. Absorbed by the New Emperor

In turbulent periods—especially during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms—new emperors sometimes took former concubines of the previous ruler into their own harems. This could be symbolic, strategic, or personal. Although frowned upon in more orthodox dynasties like the Tang and Ming, it was occasionally practiced during chaotic successions.

F. Political Elevation or Danger

A few concubines rose dramatically after the emperor’s death—particularly those who were mothers of the new ruler. These women could become Empress Dowagers, effectively ruling the empire. Conversely, some were caught in factional purges or intrigues, especially if their sons were rivals for the throne.

3. What Determined Their Fate?

| Influencing Factor | Impact on Concubine’s Fate |

|---|---|

| Rank within the harem | Higher rank = more protection and privileges |

| Whether she had children | Having a royal son often ensured ongoing influence |

| Dynasty and historical era | Earlier dynasties more likely to use sacrificial burial |

| Political stability | Turbulence led to unusual fates, including remarriage |

| Strength of natal family | Influential families could protect or reintegrate her |

4. Historical Cases That Illustrate the Spectrum

- Empress Dowager Wang (Han Dynasty): Once a concubine, she became the most powerful woman in court after her son’s ascension.

- Empress Dowager Cixi (Qing Dynasty): Entered as a low-ranking concubine and later ruled as de facto sovereign.

- Later Jin concubines (Five Dynasties): Some were absorbed by successor regimes as power frequently shifted hands.

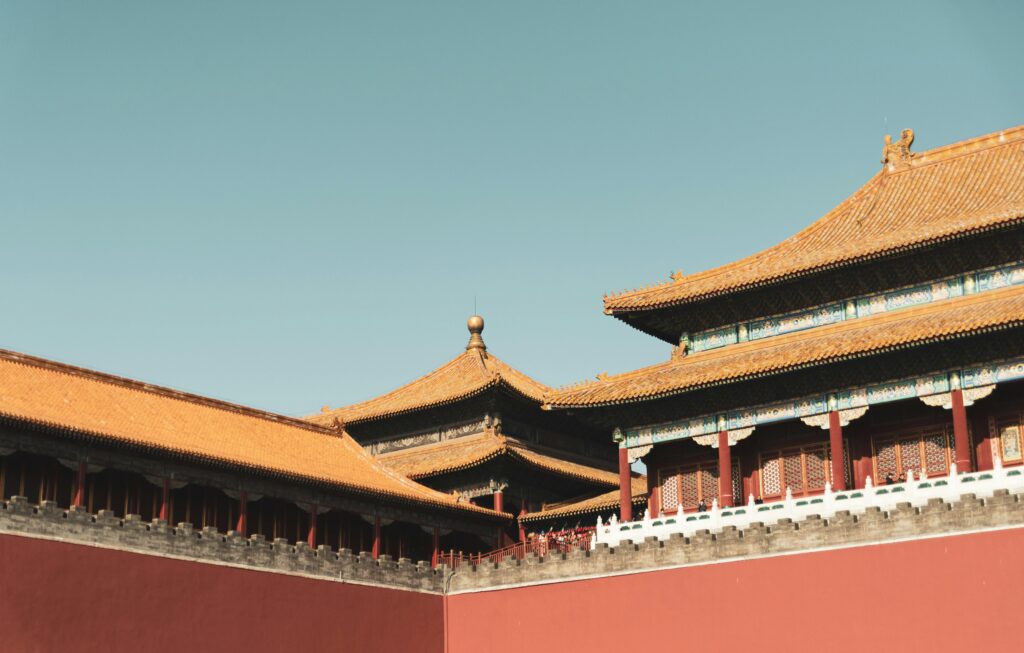

Conclusion: Behind the Golden Walls

Imperial concubines led lives of luxury—but also of uncertainty. After the emperor’s death, their futures were not their own to decide. From honored dowagers to forgotten widows, their paths reflected not just their own stories, but the political and moral landscape of China’s dynastic past. In examining their lives, we gain insight into how gender, power, and tradition intersected behind the palace walls.